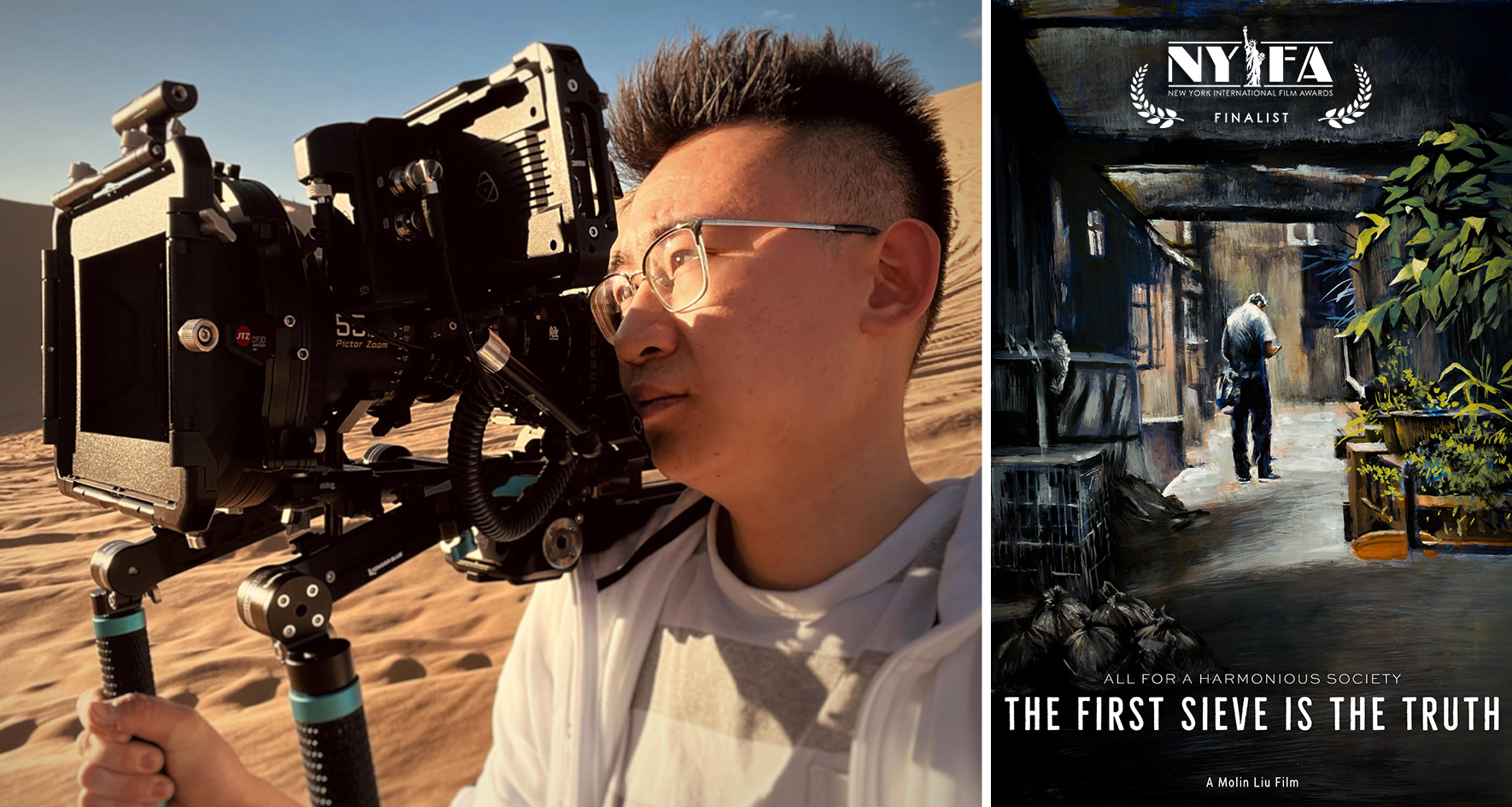

VIP Interview with Molin Liu, writer and director of the Award Winning Short Film ‘The First Sieve is the Truth’

Molin Liu is a talented bilingual filmmaker that currently works internationally in Japan, China, and Los Angeles. He directed and wrote the short film The First Sieve is the Truth. In this interview, we talk about the inspiration behind the script, the rehearsal process, and the controversy about the Chinese censorship especially in the entertainment industry. Enjoy!

Hi Molin, when did you first realize you wanted to become a filmmaker?

I started out as a photography major in college, where my only motivation was documenting, and transferring to the film department almost felt like a consequential result. To me, there isn’t a sharp line between photography and film. I have always treated them as parallel tools designed intrinsically for documenting. However, cinema is more interventional and motivational that can reshape our mindset and foster new feelings by showing us natural and raw content. My pursuit of realism film should be distinct from pure documentation. Realism film is neither a mere objective documentation in the material universal nor a mere symbolic abstraction. It’s something between them. When did I start pursuing this realness? Perhaps it was when I truly recognized our mortality, which makes everything more precious—a particular sentiment, a devoted relationship, even our evilness.

Where does the inspiration of The First Sieve is the Truth come from?

Imagine an inspired screenwriter sitting in front of a computer, writing a very intriguing moment. He spends the whole weekend brainstorming novel ideas but decides to replace them with something mediocre. Knowing that a particular line would be the most suitable and touching choice for the story, he deletes that line and changes to a less exciting option. You may feel it bizarre, yet this almost occurs daily in China. It’s called censorship—filmmakers have to revise or delete the scenes due to the “sensitivity” of certain script content to pass the examination—this was my initial inspiration.

The controversy about the Chinese censorship of the entertainment industry has lasted for decades, but it never really came to a solution. On the one hand, it is because of the government’s inaction to introduce the rating system, which is the most direct route to a resolution. Nevertheless, numerous darker contents will conceivably emerge after carrying out the rating system. These contents will not be as simple as extreme violence or horror elements but things like the inglorious history of the current political party, which could be adapted into stories with different genres. Therefore, the inaction in introducing the rating system could ascribe to fear.

On the other hand, I soon recognized something even worse than censorship—people’s self-censorship or self-restraint—an inevitable consequence of censorship. In China, a director (or any other creative role) often would immediately give up an idea due to the content’s sensitivity before the censorship even starts. In this case, censorship could be nothing more than an excuse for those trying to vindicate themselves from being unimaginative. Still, mostly, it is due to the numbness caused by the rigorous system. Such self-restraint is no longer just happening in the film industry but extends to many other areas like reality shows and music. Oftentimes, the television station will modify the script (even for “unscripted” shows) to meet the criterion, not to mention the sudden absence of an original lyric in the subtitle during music programs. We may then find it difficult to determine the real motivation for such restriction—Is it an externally-generated matter or vice versa?

Can you describe your creative process when writing a script?

It took me more than four months to concretize the abstract idea in my mind into a feasible outline, which was the most energy-consuming step during the entire creative process. Initially, I was working with a screenwriter who had already provided me with a script. During the revision process, however, I came to realize that the script was unable to implement my abstract idea—over the multiple revisions, I was unconsciously leading the overall theme and structures in another direction to the point that it needed a complete rewrite. After that, I was on my own. I deleted nearly ninety percent of the content with only one sentence left: “Your content was removed due to a violation of community guidelines,” which was eventually embedded in the film’s last shot. I then began to design each scene backward based on that presumed ending.

I went to the same coffee shop (now replaced by another store) every time to brainstorm the outline simply because my mind was a complete blank at home when I had no choice but to stare at the white wall. Sometimes, a line could pop up in my mind after I saw a random thing outside. Another reason for working at that café is because of a bookstore nearby. Thinking back then, I might have spent more time in the bookstore reading than in the café writing—1984 by George Orwell, Clandestine in Chile: The Adventures of Miguel Littín by Gabriel García Márquez, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by Edwin Abbott Abbott, and The Sound of the Mountain by Yasunari Kawabata. These books must have benefited my writing process since most are related to social subjects. But such a bookstore routine might just be an excuse for my procrastination.

I usually worked out a draft of the outline every 10 to 14 days, after which I would present it to a friend for her honest opinion and sometimes harsh criticism. Occasionally I would overthrow and rewrite the draft partially or entirely before seeing her. That friend eventually became the co-screenwriter of this film. Though I was constantly making small changes until the principal photography, It only took me a few weeks to work out the script’s first draft, which I thought would take longer. I ascribe such efficiency to the explicit outline that allows me a clear and visualizable sense of the film’s structure so that I know who will do what and by when—the rest is just fill-in-the-blank.

Where and when did you shoot the film?

We shot the film in Chongqing, a city that has rolling hills, architectures with substantial height differences, the roaring waves from the Yangtze River, and those dark, contracted, many-angled alleys—it fits perfectly for a crime movie, and such high-and-low contrast naturally enabled The First Sieve is the Truth to represent the class hostility

The director Molin Liu and the official poster of ‘The First Sieve is the Truth’ – www.molinliu.com

What is the message you wanted to communicate to the audience?

Society will become precarious when it only permits a single ideology. However, what’s even worse is the acquiescent self-censorship and self-limiting among people that will eventually deprive us of our ability to embrace pain and evil, two critical components to keep this society from collapsing.

What is the most challenging project you’ve completed? What did you learn from it?

It must be the one-take film I wrote and directed in New York City at the end of 2022. It is a transitory moment of the unstable psychological experience of a Chinese illegal immigrant who lives in Flushing, struggling to pay off her husband’s smuggling fee. Aiming to provide the audience with the most immersive viewing experience of her psychological changes, we shot it in one take, making this project significantly more challenging.

The whole point of editing is to provide the audience with decisions and paths that they (or, in some cases, the director) would actually make and follow in the real world, which could deprive the audience’s rational and independent thinking ability since none of that advance arrangement (editing) would apply to the actor who only lives in that moment. Therefore, forcing the audience to watch the entire film in one take can let them sense the most natural emotions and the most intuitive motivations.

In this case, we had to design the blocking in advance, which was not as difficult as I anticipated compared to maintaining the actors’ emotions at a similar level for every take. This film tells a very emotional story requiring actors to transform instantly from one feeling to another, and the actors couldn’t guarantee such emotional changes would happen on every take. After all, it makes the actors’ emotional control significantly harder by knowing that someone’s mistake usually means starting from the top.

To me, the only two methods to ensure such emotional consistency are to think of as many realistic relative personal experiences as possible for direction giving and to make sure you fully resonate with the script—you don’t want the actors to sense anything untruthful, unconfident, and self-doubting from you.

Besides the emotional consistency, a one-take film would also challenge the writing process in which all the scenes must assemble a continuous storyline—no time jumping. As that being said, a one-take film can either restrict or enrich the creative process—depending on what you can make out of it.

Who are the directors that inspire you the most?

I used to fall asleep when watching Edward Yang’s films—it was too mundane. Ironically, I started watching his film recently before bedtime, during lunchtime, and every new years eve. Occasionally, there are tears. I can’t remember when these screenings became routine. During the nearly 3-hour-long duration of watching Yi Yi, I was astounded so many times by Yang’s unsentimental vision, almost like watching a news report from an irrelevant observer. Every time after watching his film, I knew something must have happened, yet somehow I was incapable of describing it precisely. It was never about a particular event but about living someone else’s entire life. I hope one day I can make films that, underneath the seemingly impassive exterior, there is no sense of permanent save in appearance but are as eternally fluid as the sea.

Since college, I have enjoyed reading Gustave Le Bon’s books, which significantly assisted the creative process of The First Sieve is the Truth. Gustave Le Bon is not a filmmaker but a French polymath who contributed enormously to psychology and sociology. He believes that an unconscious collective mind will emerge in a crowd situation, affecting the individual’s behavior unexpectedly. In this “collective mind” situation, the individual will unconsciously relinquish the rational and independent thinking capabilities and would eventually start “acting based on their emotions and fears, often in ways they would not have done based on their individual beliefs.” Definitely read Gustave Le Bon’s books if you are interested in anything about human behavior.

You are a bilingual filmmaker; how do you think this affect your work? Do you think that being fluent in more languages helps you reach a wider audience?

Learning a new language does not directly benefit my creative process but can offer me a more critical and comprehensive mindset. Part of my reason for being bilingual is also just in case someday I can shoot films overseas.

What do you do in your spare time? What are the activities or hobbies that nurture you the most as an artist?

Part of my reason for transferring out from the photography department is that I love photography too much. If shooting portraits in the studio had become my everyday routine, I would have given up on photography three years ago. Likewise, one thing that helps me the most in being creative as a filmmaker is doing something completely irrelevant to the film, which allows me a more objective approach instead of personal and sentimental when shaping an idea from scratch.

What’s the best piece of advice that was ever given to you?

Be true to yourself.

The character of the secretary, who is supposed to be the victim in your film, turns out to be the real villain. Can you tell us more about this choice?

The secretary inconspicuously turns from the victim to the villain quite early—when we see his scandal pictures. The psychological journey between the secretary and the thief is rather parallel since no one in this film is merely a victim or a villain in the traditional sense. For instance, righteous strangers chase after the thief but soon change their minds—they are just as accurate as our natural behaviors. I want this film to be as calm and unvarnished as possible.

Why does the thief choses to risk his own life to get the truth out?

This is a question I asked myself the most when I was designing the ending—in what way can it affect people most realistically? Initially, our motivation in making him do the right thing was to shake off his evilness and create some hope, which would have enabled a stronger antithesis between the two characters. But then we realized that no bad guy would suddenly discover a force for good from a moral perspective. Therefore, to not make the character stiff or far-fetched, we added a scene where the secretary gives counterfeit money to the thief, which thus grants the thief a more realistic motivation when uploading the photos—simple-minded revenge.

How did you work with the actors Wei Wu and Zhenyu Li during filming? Did you give them space to improvise, or do you usually prefer to rehearse before filming?

Having rehearsal for every scene is necessary, especially for complicated settings like chasing that involve considerable uncertainties. It simply makes the shoot more efficient. Rehearsal is also beneficial for the actors to get to know each other, understand and analyze one another, and develop cognition and curiosity for each other to reach emotional depths together. Also, giving them time to try out the scene before the shoot is always good—they sometimes improvise with different postures and lines that I never thought of.

What’s next for you? What are you working on now?

I am working on the post-production of a new one I shot at the end of 2022. I am also brainstorming a feature, which will be a VERY long journey.

Also, I love collaborating! Check out my directing & cinematography reel at my website: www.molinliu.com. It is also where I post new work regularly. Please contact me via my email at liumolin82(at)gmail.com or my Instagram.

Follow Molin Liu and his projects on: