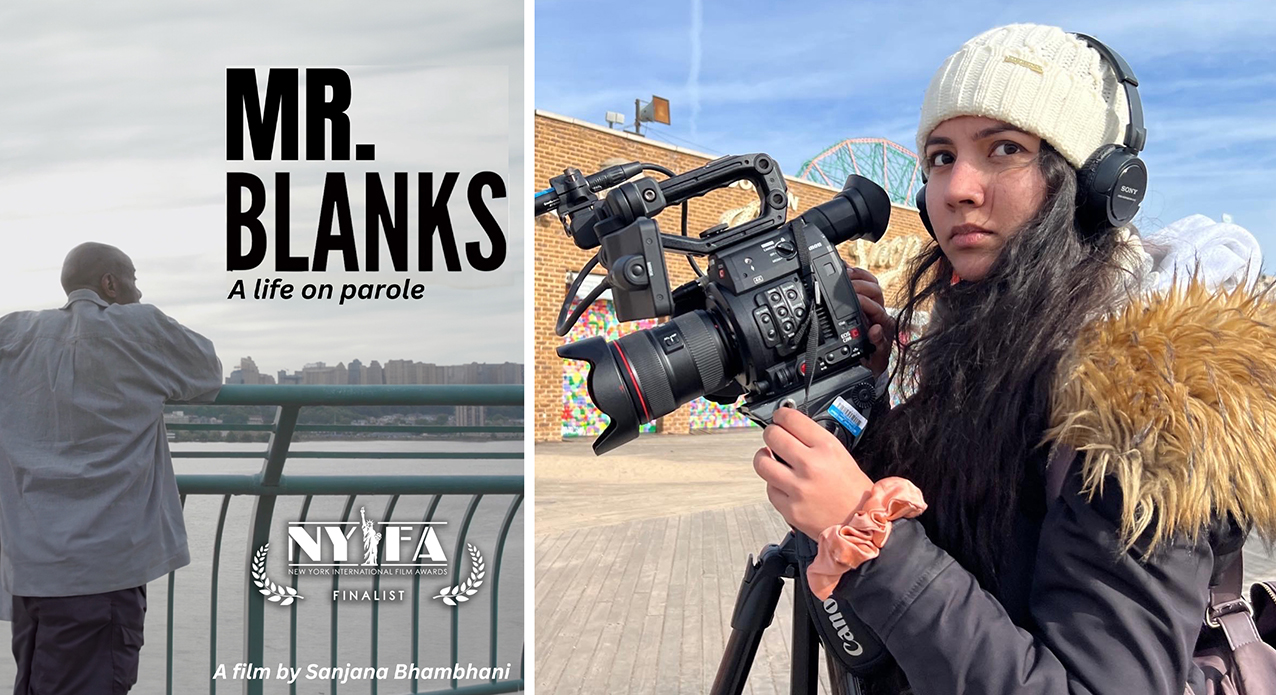

Interview with Sanjana Bhambhani, director of the Documentary Short ‘Mr.Blanks: A life on parole’

Hi Sanjana! ‘Mr.Blanks: A life on parole’ has been recently named a Finalist in the category ‘Best 1st Time Director – Short’ at the New York International Film Awards. Could you tell us more about this project?

Hi! And thank you so much for recognizing ‘Mr.Blanks: A life on parole’. It has meant a lot to Mr. Blanks, Ms. Colon and myself.

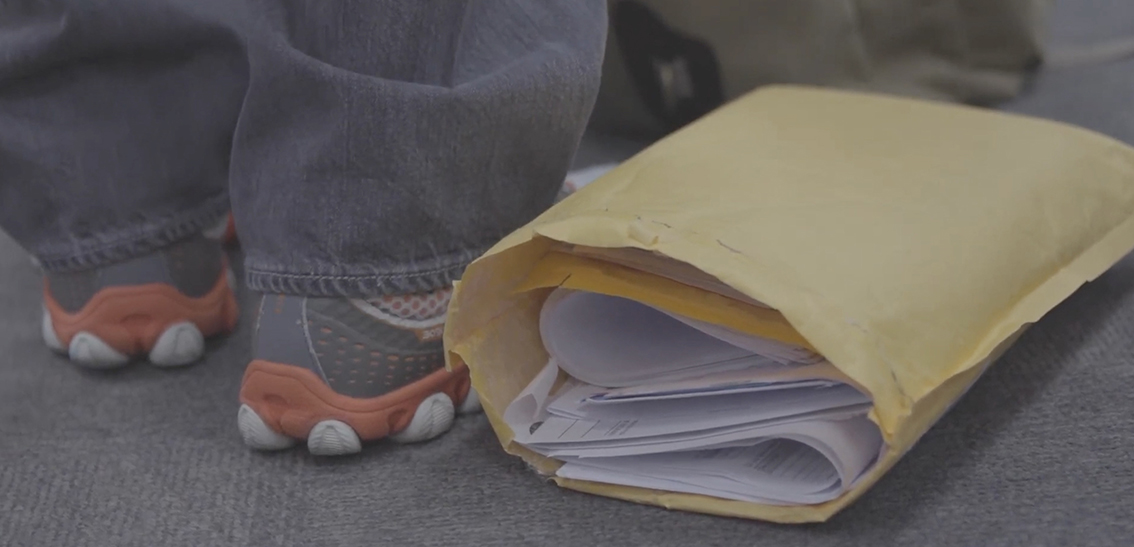

The documentary is about Mr. Anthony Blanks, a now 71-year-old man who was incarcerated for over 46 years and faced 23 parole boards before he was released in October of 2022. Since then, he has been in search of stability: a family, a source of income and the technical skills he needs to survive in this new, modern world.

Unfortunately, those he considered family before he was incarcerated have now passed away. And their children never got to know him, so they haven’t really been in touch. Finding a group of people who can support his transition back to society, who can not just help him navigate the system but also be there for him emotionally, has been a challenge.

Where money is concerned, ageism means few employers are willing to hire him, especially with a criminal record. Add to that the fact that our modern world centers on technology, and Mr.Blanks isn’t left with all that much to build a life for himself.

But he hasn’t given up. He’s finding family in those at his transitional housing and among advocates in the parole justice space. He’s been applying for benefits to help with his medical bills, and attending computer literacy classes at his local public library. All in the hope that one day he can have some normalcy in his life.

The director and journalist Sanjana Bhambhani and the official poster of ‘Mr.Blanks: A life on parole’

Tell us a bit about your background. When did you decide you wanted to work in the film industry?

I’m actually a journalist, so not originally from the film industry. Currently, I produce videos about history, technology, climate change and more for the BBC.

My first time working in video was when I took an elective during my semester abroad in Madrid. I was a Politics major at NYU but I’d always been fascinated with video editing. To the extent that playing with iMovie to produce home videos counts. I wanted to explore that more and this felt like the perfect opportunity.

I was lucky to have two incredible documentarians for professors: Almudena Carracedo and Robert Bahar. They’re the Emmy and Goya winning filmmakers behind “You Are Not Alone”, “The Silence of Others” and “Made in L.A.”.

In that class, called ‘Madrid Stories’, I worked with two of my batchmates, Stuti Bagari and Minjong Kim, to produce a short piece about one of Madrid’s graffiti artists. From the moment I landed in the city, I saw works of graffiti on walls and storefronts everywhere. But on looking into it, I came to learn that doing graffiti is illegal. That dichotomy set us on a path to finding an artist who would be willing to speak to that disconnect.

There were a number of reasons we were ill-equipped at the start of that process, to handle such a story. Among them was the fact that all three of us were still learning to speak Spanish and the person we ultimately made our film about – his artist name is “Joen” – didn’t speak English. Because graffiti artists can be fined or even receive a prison sentence, Joen understandably didn’t want to show his face or use his name, so we did our best to avoid both. And from a technical perspective, no one on our team had used professional filming equipment or editing software before.

But after three months, we ended up with a 6-minute piece titled “Por Amor Al Arte” or “For the love of art” – a quote by Joen in the film – that we put up on Vimeo.

After that experience, I knew I wanted to continue producing videos and sharing stories. For about a year-and-a-half, as a passion project, I produced daily short form videos for social media – TikTok, Instagram, YouTube – where I would share stories of women who had been left out of our history books. The account is called @womenofhistory on TikTok and I still post when I am able. But I didn’t re-enter the world of documentary till later in graduate school in 2023, which is when I began working on “Mr.Blanks: A life on parole”.

What did you enjoy the most about working on this documentary? What did you find most challenging?

I think the hardest part of making a documentary like this is experienced by the person the film is about. Mr. Blanks was going through an incredibly difficult time in his life, emotionally and physically. He had medical concerns that needed to be addressed, he needed a job or some kind of social safety net to stay financially afloat and he was navigating a completely different world than the one he left behind, without a family to support him.

Amidst everything else going on, he still wanted to show people what the post-parole life for the elderly is actually like.

It must be no small decision to open-up about one’s hardships the way Mr. Blanks did, as someone who has experienced incarceration for almost five decades, especially with the stigma around having been in prison in our society.

He made the time for interviews, let me follow his visit to the pharmacist, City Island, and his evening stroll in a nearby park. He facilitated the opportunity for me to sit in on community meetings at his transitional housing facility so I could get to know the community better. He made time for phone calls that helped me understand how to share this story in the most well-informed way I could.

And all I can hope is that I did justice to the time he invested.

Do you have any fun facts from the shooting you would like to share?

I was introduced to Mr. Blanks by his friend and a parole justice advocate who is also in the documentary, Jeannie Colon. And she referred to him as Mr. Blanks when speaking with me, so that’s what I started calling him.

One day, when I went to visit Mr. Blanks at his transitional housing facility, someone at the community meeting asked me who I was there to see. I said, “Mr. Blanks” but they looked at me confused. Then I said “Anthony Blanks”. They still weren’t sure who I meant. I wasn’t sure why: Mr. Blanks had lived in that residence for a few months now. The last time I visited, he seemed to be friendly with everyone there. After a bit of back and forth, the person I was speaking to went, “you mean Tony?”

It hadn’t occurred to me that not everyone calls him, “Mr. Blanks”. Except when they were speaking to me about him, because I used that name. I looked back and noticed Mr. Blanks had also been signing texts off with “Tony” or “Anthony”. But it just never felt right to use a name other than ‘Mr. Blanks’ and so that’s what I call him to this day.

And that became the name of the documentary.

What keeps you inspired to continue working as a filmmaker?

The people whose stories I am given the privilege of sharing and the people who I get to work with in the process!

A mentor of mine once told me “the most important thing in life is relationships” and I’ve never seen something proven true more quickly before my eyes. The people involved in the process of storytelling are what make the work worth doing.

Do you have a dream project or someone you would like to work with one day?

I’m relatively new to the documentary space so the disappointing answer to that is, I don’t know yet.

But as long as I can keep working on projects that participants and audiences find meaningful – hopefully ones that can facilitate positive change – and I can continue working with people who are as talented, passionate and inspiring as the colleagues I have had, I’d hopefully feel like I’m putting work out into the world that is impactful.

What is the message that ‘Mr.Blanks: A life on parole’ conveys?

People might take away different messages from what they see but I hope the documentary can at least shed some light on what elderly parole looks like, especially for those unfamiliar with the carceral system in New York. It’s a tremendously difficult experience, more so for those without a community to support them.

Perhaps on a larger scale, I hope the documentary can speak to the side of human beings that wants to be forgiving and help rehabilitate rather than further the punitive system we live in today.

What’s next for you? What are you working on right now?

I am currently helping gather material for and editing a documentary but I’m not sure how much more I can share right now, unfortunately.